Your support helps preserve our history and keep heritage alive in Dunfanaghy. Support Our Work.

Your support helps preserve our history and keep heritage alive in Dunfanaghy. Support Our Work.

The history of the Dunfanaghy Workhouse is closely tied to the Poor Law system, the Great Irish Famine and the lived experiences of local communities. This page explores how the Workhouse came to exist, how it functioned and how it continues to shape understanding of this period in Irish history.

The Poor Law system was introduced to Ireland under the Poor Law Act of 1838, following similar legislation in Britain. Its purpose was to provide relief for the most destitute members of society through the creation of Poor Law Unions.

Each Poor Law Union consisted of a group of townlands, with a central workhouse where relief was administered. By 1845, Ireland had 130 Poor Law Unions. In 1831, the Dunfanaghy Poor Union included areas such as Dunfanaghy, Creeslough, Derryreel, Falcarragh and Derryveagh. Census records show the population of the union at that time was 15,793.

Workhouses were introduced to Ireland as part of the Poor Law system. Most were designed by George Wilkinson, Chief Architect to the Poor Law Commission, and followed a recognisable layout and appearance.

A typical workhouse included reception areas, dormitories, workshops, an infirmary, school rooms, kitchens and enclosed yards surrounded by high stone walls. A Board of Guardians oversaw the operation of each workhouse, including finances, staffing and policy decisions. These boards were made up of locally elected members, along with a Justice of the Peace.

Daily operations were managed by the Master of the Workhouse, supported by staff such as the Matron, Porter, Clerk, Schoolmistress, Doctor, Nurse and other officers.

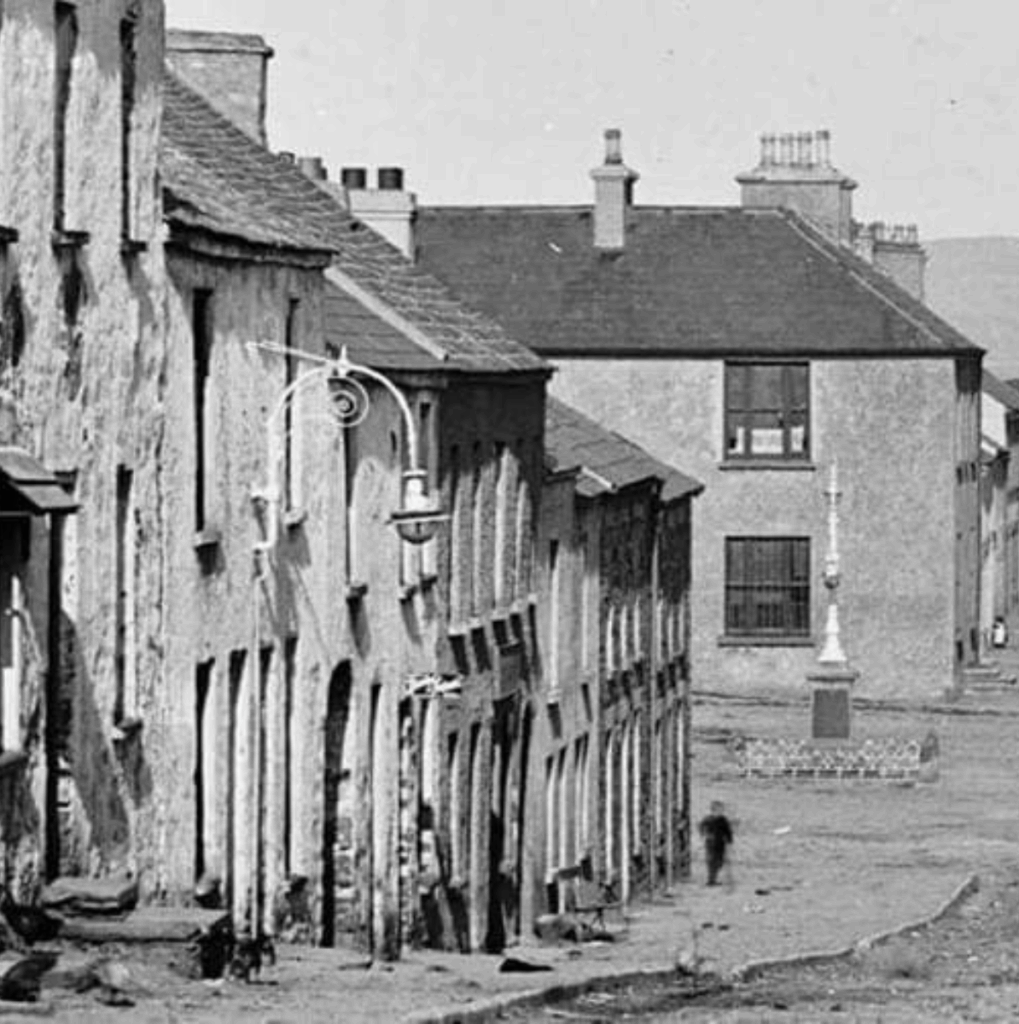

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse opened on June 24th, 1845, and was one of eight workhouses in County Donegal. Conditions were basic, although the Board of Guardians insisted on stone flag floors rather than earthen ones.

The building cost £5,000 to construct, funded by a loan from the Poor Law Commissioners and later repaid through local poor rates. Local stone was used, including limestone quoins from Ballymore Quarry. Unlike many workhouses, the Dunfanaghy Workhouse featured a split entrance block.

When it first opened, only five paupers were admitted.

The Dunfanaghy Board of Guardians consisted of 22 men drawn from local landowners, merchants, gentry and Justices of the Peace. Prominent local landlords such as Stewart, Olphert and Hill were members, alongside merchants including William Ramsey. This board met weekly and was responsible for overseeing the administration of the Workhouse.

Members of the first Board of Guardians included:

Alexander R. Stewart, Neal Lafferty, William Smyth, Denis Cannon, Wybrants Olphert, Michael Boyle, Edward Coll, James Gallagher, George V. Hart, George Weir, Thomas Lurgan, Lord George A. Hill, Captain Gilbert, Denis Sweeney, Bernard Rodden, Patrick O’Donell, William Ramsey, Thomas Robinson, Edward McElroy, Francis Mc Garvey, Patrick McFadden and Tinlay Ashe.

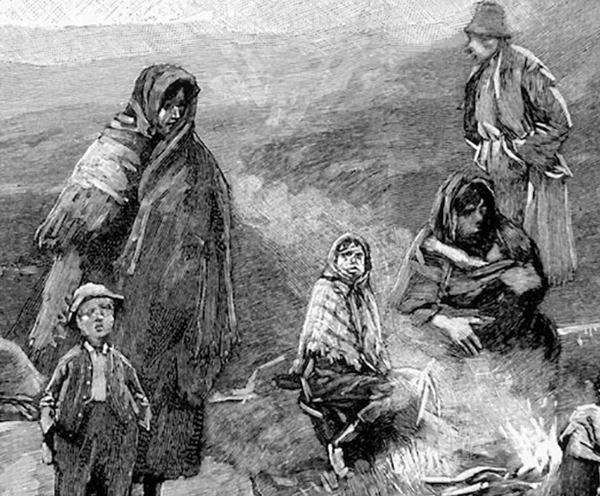

Between 1845 and 1852, Ireland experienced the Great Irish Famine, known as An Górta Mór. While food shortages were not uncommon in Ireland, the failure of the potato crop in 1845 led to catastrophic consequences.

The cause was a fungal disease called Phytophthora infestans, commonly known as blight, which arrived via imports from North America. At the time, over one third of Ireland’s population relied on the potato as a primary food source. In Donegal, this figure was closer to nine tenths of the population.

When the Dunfanaghy Workhouse opened in 1845, it housed only five inmates. As crop failures worsened, admissions rose sharply. By 1847, known as Black 47, the Workhouse was expanded and outdoor relief was withdrawn.

By 1851, 481 paupers were living within the Workhouse. Although the Dunfanaghy Poor Union escaped the very worst effects of the famine compared to other areas, hardship was widespread. Diets consisted mainly of soups and stews provided through poor relief, with coastal communities around Sheephaven relying heavily on fish, shellfish and seaweed.

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse closed in 1918, four years before the Poor Law system was formally dissolved in 1922. The building was later used as a co operative and for storage before falling into disuse.

In 1989, the site was declared a heritage site. In 1995, exactly 150 years after its original opening, the Workhouse reopened as the Donegal Famine Heritage Centre.

Step inside the spaces where these stories unfolded. Our Famine Exhibition brings the history of the Dunfanaghy Workhouse to life through audio storytelling, original rooms and personal accounts.